.

.

Fabian Peake: Staring at the Silence

Opening: Friday 24th June 2022, 4pm

Chiesa dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Via S. Giovanni e Paolo, 5, 06049 Spoleto

Visible during opening hours Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays 11:00–13:00, 16:00–19:00.

Project by Gertrude Gibbons in collaboration with Franco Troiani (Studio A'87). Text and curated by Gertrude Gibbons, with the patronage of the Municipality of Spoleto.

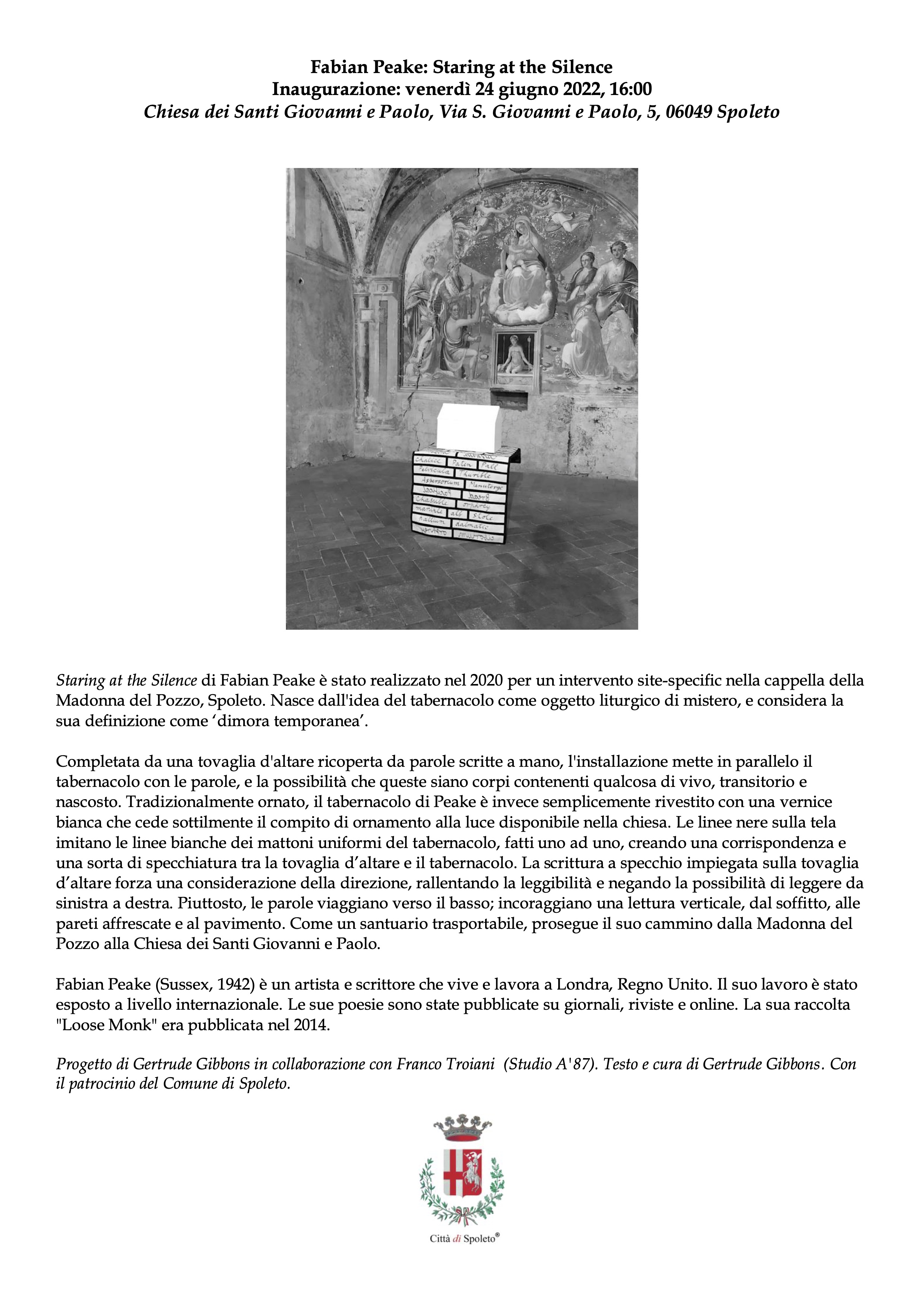

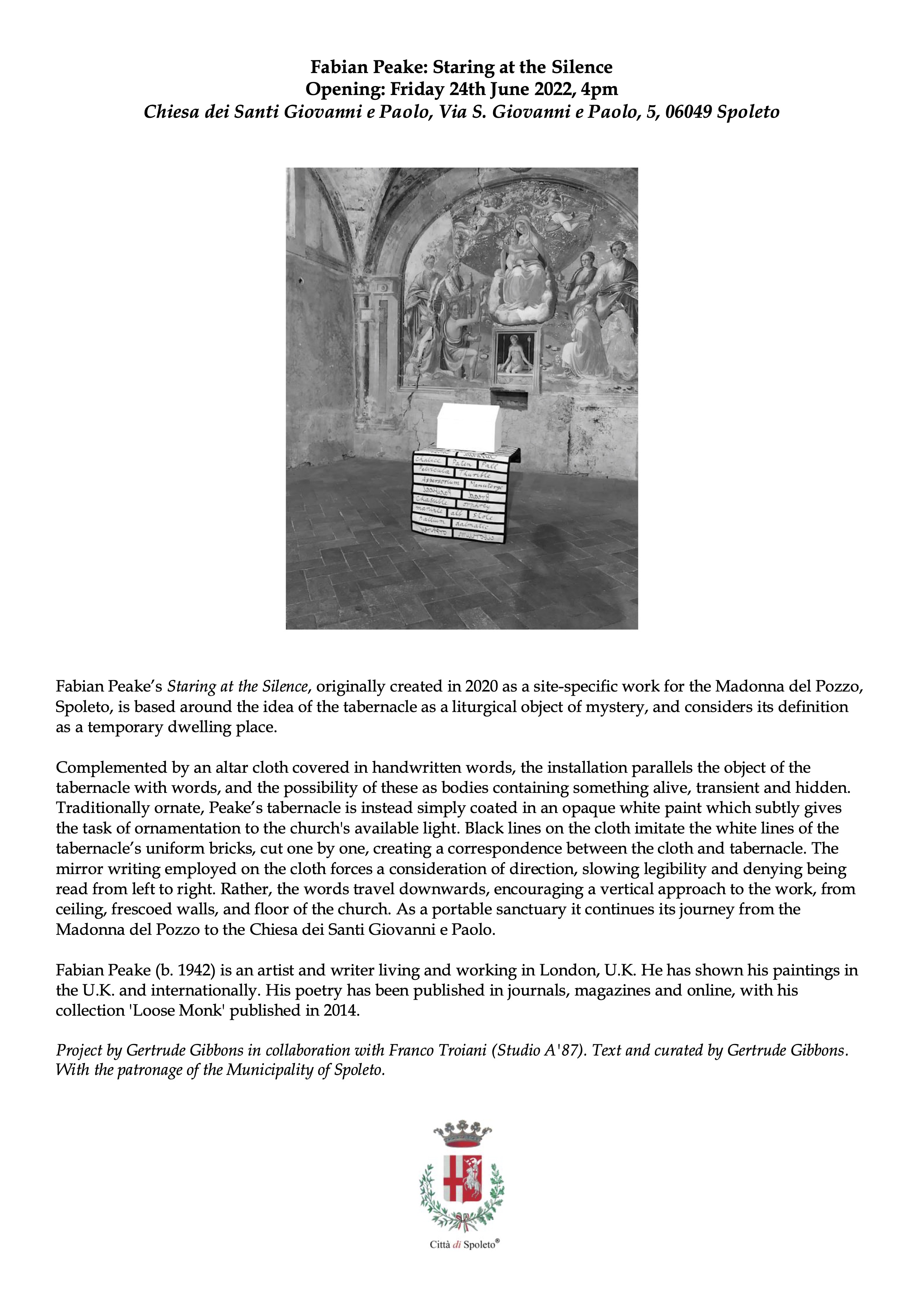

Fabian Peake’s Staring at the Silence, originally created in 2020 as a site-specific work for the Madonna del Pozzo, Spoleto, is based around the idea of the tabernacle as a liturgical object of mystery, and considers its definition as a temporary dwelling place.

Complemented by an altar cloth covered in handwritten words, the installation parallels the object of the tabernacle with words, and the possibility of these as bodies containing something alive, transient and hidden. Traditionally ornate, Peake’s tabernacle is instead simply coated in an opaque white paint which subtly gives the task of ornamentation to the church's available light. Black lines on the cloth imitate the white lines of the tabernacle’s uniform bricks, cut one by one, creating a correspondence between the cloth and tabernacle. The mirror writing employed on the cloth forces a consideration of direction, slowing legibility and denying being read from left to right. Rather, the words travel downwards, encouraging a vertical approach to the work, from ceiling, frescoed walls, and floor of the church. As a portable sanctuary it continues its journey from the Madonna del Pozzo to the Chiesa dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

[English - Scorrere per l'italiano]

Site Specificity and a Temporary Place of Abode: Fabian Peake’s Staring at the Silence for the Madonna del Pozzo, Spoleto, 3-23 September 2020 for ‘OPUS & LIGHT’ project by Franco Troiani (STUDIO A’87) curated by Gertrude Gibbons

A site-specific work is anchored to place. Its movement poses a problem; its physical transference prompts a possible shift in its concept. Made for a particular location, growing from ideas provoked by a place’s unique characteristics, the independence of a site-specific work is ambiguous. Such a work, by reflecting on its situation within its object, is naturally self-reflexive of its nature as a work exhibited in a certain location. Might a work only ever be exhibited there, for this site? Or might it have the capacity to live independent of its location in some form, so that the site simply becomes part of the work; part of its subject, lent new meaning in a context foreign to its origins. Realised in response, and as a conversation with, a designated dwelling place, a site-specific work incorporates two aspects: the site, and the potentially independent work which grows from it.

In September 2020, the chapel of the Madonna del Pozzo, home to the smallest museum of Umbria, Italy, became temporarily home to another home. This unique site, filled with fifteenth and sixteenth century frescoes, has been used for regular artistic interventions since 1997 as part of a project ‘Opus & Light’ conceived by the Spoleto artist Franco Troiani. Staring at the Silence, by the British artist Fabian Peake, is a site-specific work for this chapel, based around the idea of the tabernacle as a liturgical object of mystery, considering its definition as a temporary dwelling place. It contemplates its situation within a city layered with rich artistic history, in which voices of the past are visible as they form palimpsests across streets and buildings; where wall drawings of the 1970s and frescos of the fifteenth century converge and converse, encouraging dialogue across era. The fresco on the back wall is attributed to Bernardino Campilio dated 1493, a significant native painter of Spoleto. The contemporary interventions interrupt, complement and juxtapose the space, its rough walls and dominating stone altar. Inescapable in this tiny museum is the well in the centre of the floor, the chapel’s namesake (‘pozzo’ meaning ‘well’), originally believed to have miraculous healing properties, and over which the chapel was built. Indeed, the local people of Spoleto retain a deep respect for this place, not simply for its religious connotations, but also for its new role in displaying work by artists from various nations, generations, and disciplines. In appreciation for an installation, flowers or notes might be found by the door of the chapel. This little space reflects, in miniature, characteristics and an identity of the historic cultural city of Spoleto.

At a period when in-person travel was difficult, this portable sculptural installation responded to ideas of this site from a distance. When I initially spoke to Peake about making a work for this space, we discussed the particularities of its location; its exhibitions’ resonance with atmosphere, cultural history, and the voices past and present of the area. The abode of these ideas ultimately made its way as an object from London to this chapel neighbouring the Spoleto city wall, bordering the ancient Roman road, the Via Flaminia, which runs from Rome to Rimini, city to coast. Walking along Spoleto’s historic streets, feet fall on the traces of footsteps left by previous visitors and inhabitants, those left by Fra Filippo Lippi, Michelangelo, through to Alexander Calder, David Smith and Sol LeWitt. With the famous Festival dei Due Mondi (Festival of Two Worlds) initiated in 1958 by Gian Carlo Menotti, this area of Italy seems bound to art and international, interdisciplinary, and cross-generational conversations. It is a site of dialogue, and to make a site-specific work for Spoleto, for the tiny museum symbolising the conversations of Spoleto, is to respond to its voice as a whole; its location as an abode for travelling voices which leave trace in their passing. Walking past the Madonna del Pozzo at night, lit by a yellow light, it appears a steady but subtle presence. Cars throw diagonal lights across the altar, casting shadows across the painted faces, illuminating them for an instant before they vanish again. The site, which has steadily survived centuries of earthquakes, seems to come and go, allowing the natural ebb and flow of pedestrians to reflect on the passing exhibitions.

*

Rules dictate the container must be opaque, ornate and locked. It sits closed and central upon the altar, where the eye is directed towards it, encouraged to gaze for extended periods at its decorated surface and contemplate what it holds. Defined as a temporary dwelling-place, a tent, hut, or booth, the word “tabernacle” can also be used as a verb, meaning to dwell or enshrine. In this way, the focus is either on the inside space, the potential place of habitation; or else the emphasis falls on the walls which shroud and protect. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the noun is associated with the human body as the temporary abode of a life or soul: “tabernacle” refers to a body, containing something alive, transient and mysterious. The body acts as a shrine to something that cannot be seen; its surface obscures what should not be seen. Its solid form is always suggestive; pointing towards something within.

Fabian Peake’s tabernacle in Staring at the Silence is not ornately decorated, yet neither is it plain. Its opaque white covers an intricate pattern of bricks, carefully hand cut one by one, ensuring overall uniformity. Neither matt nor glossy, the paint allows a subtle reflection of light; a small glow in the shadows of the chapel. The paint surface uses the light and dark of its surroundings to decorate it, leaving the task of ornamentation to the chapel which holds it. Subtlety of available light is utilised in Peake’s corresponding altar cloth too, where the lining of the cloth, unseen as it faces the altar, is made of purple satin. The reflective quality of the satin gives the possibility of a glimpse of purple, like coloured light through stained glass, upon the stone of the altar. This draws attention to the importance of what is behind; the possibilities of what is contained by the obscuring wall or veil. The cloth itself marks a contrast with the tabernacle’s uniform surface, covered with red handwritten words which, in their cursive hand, make use of the shapes of letters as ornamentation. Black lines divide the words on the cloth one by one, mirroring the white lines of the tabernacle’s bricks. This suggests the possibility of a connection between the words contained by the bricks of the cloth, and the mystery of what the tabernacle contains.

Traditionally, it is the Eucharist, the Body and Blood of Christ, that is held obscured by the walls of the tabernacle. The Eucharist’s temporary abode here echoes Christ’s temporary dwelling among humankind: the temporary period in which “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us”, just as words themselves give the transience of an idea temporary flesh.[i]In fact, St Augustine uses the nature of language as a means to describe the nature of the human soul. He claims that in a word, “just as in some living being, the sound is the body and the meaning is, as it were, the soul”.[ii]This indicates a parallel between places of temporary abode: words are bodies, and bodies are temporary dwelling places. The tabernacle is a body and it is a word, and its body might be used as symbolic of the nature of words as bodies. Martin Heidegger, discussing the poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin, suggests words are potential dwelling spaces: “Poetic creation, which lets us dwell, is a kind of building”.[iii]It is this connection to words that Peake’s work comments upon. The tabernacle contains and conceals; likewise the words on the cloth, many of which are obscure, are surfaces veiling whatever meaning they contain. Written as ornamentation, their curves and lines are decorative veils enshrining a mystery.

These decorative words are designed to be looked at rather than read, and their task in this manner is ensured by the difficulty of reading them. Not only are they obscure words in cursive hand, but many of them employ mirror writing. This mirroring forces a consideration of direction. While it denies any attempt at looking from left to right, the words are never reflected across the horizontal; they run downwards, directing the eye lower and lower, pointing towards the chapel’s central well. This hole, black and surfaceless, becomes another mirror to the white and walled tabernacle. Yet this well also contains, evokes and signifies, such that the walls of the shrine itself have been built around it, to house it, giving it a place of abode.

Perhaps a site-specific work, made for a unique place, becomes a memento of that place. It becomes another word, another voice leaving a trace, to be repeated, echoed or rephrased in the mouths of others. It works, perhaps, in the form of performance; finished once removed from the site, it remains, in its object, a form of documentation of its temporary belonging there.

[Italiano]

Fabian Peake: Staring at the Silence

Inaugurazione: venerdì 24 giugno 2022, 16:00

Chiesa dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Via S. Giovanni e Paolo, 5, 06049 Spoleto

Progetto di Gertrude Gibbons in collaborazione con Franco Troiani (Studio A'87). Testo e cura di Gertrude Gibbons, con il patrocinio del Comune di Spoleto.

Staring at the Silence di Fabian Peake è stato realizzato nel 2020 per un intervento site-specific nella cappella della Madonna del Pozzo, Spoleto. Nasce dall'idea del tabernacolo come oggetto liturgico di mistero, e considera la sua definizione come ‘dimora temporanea’.

Completata da una tovaglia d'altare ricoperta da parole scritte a mano, l'installazione mette in parallelo il tabernacolo con le parole, e la possibilità che queste siano corpi contenenti qualcosa di vivo, transitorio e nascosto. Tradizionalmente ornato, il tabernacolo di Peake è invece semplicemente rivestito con una vernice bianca che cede sottilmente il compito di ornamento alla luce disponibile nella chiesa. Le linee nere sulla tela imitano le linee bianche dei mattoni uniformi del tabernacolo, fatti uno ad uno, creando una corrispondenza e una sorta di specchiatura tra la tovaglia d’altare e il tabernacolo. La scrittura a specchio impiegata sulla tovaglia d’altare forza una considerazione della direzione, rallentando la leggibilità e negando la possibilità di leggere da sinistra a destra. Piuttosto, le parole viaggiano verso il basso; incoraggiano una lettura verticale, dal soffitto, alle pareti affrescate e al pavimento. Come un santuario trasportabile, prosegue il suo cammino dalla Madonna del Pozzo alla Chiesa dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Fabian Peake // Staring at the Silence

Madonna del Pozzo, Spoleto, 3-23 Settembre 2020

“OPUS & LIGHT” Progetto di Studio A'87 // con il Patrocinio del Comune di Spoleto. A cura di Gertrude Gibbons.

Le regole impongono che il contenitore debba essere opaco, decorato e chiuso. Si trova chiuso e centrale sull'altare, dove l'occhio è diretto verso di esso, incoraggiato a guardare per lunghi periodi la sua superficie decorata, e contemplare ciò che contiene. Definita come una ‘dimora temporanea’, una tenda o una capanna, la parola “tabernacolo” può anche essere usata come verbo, che significa abitare o avvolgere (custodire). In questo modo, il focus è o sullo spazio interno, potenziale luogo di abitazione; oppure l'enfasi è sui muri che avvolgono e proteggono. Secondo l’Oxford English Dictionary, il sostantivo è associato al corpo umano come dimora temporanea di una vita o di un'anima: “tabernacolo” si riferisce a un corpo, contenente qualcosa di vivo, transitorio e misterioso. Il corpo funge da santuario per qualcosa che non può essere visto; la sua superficie oscura ciò che non dovrebbe essere visto. La sua forma solida è sempre suggestiva; indicando qualcosa dentro e dietro.

Il tabernacolo di Fabian Peake in Staring at the Silence non è riccamente decorato, ma non è nemmeno semplice. Il suo bianco opaco (vale a dire, non trasparente o traslucido) copre un intricato motivo di mattoni, accuratamente tagliati a mano uno per uno, garantendo l'uniformità complessiva. Sebbene non sia lucido, la vernice consente un sottile riflesso della luce; un piccolo bagliore nelle ombre della cappella. La superficie verniciata utilizza la luce e l'oscurità dell'ambiente circostante per decorarla, cedendo il compito di ornamento alla cappella che lo custodisce. La sottigliezza della luce disponibile è utilizzata anche nella corrispondente tovaglia dell'altare di Peake, dove la fodera del tessuto, non visto perché è rivolto verso l'altare, è di raso viola. La qualità riflettente del raso dà la possibilità di intravedere il viola, come la luce attraverso il vetro colorato, sulla pietra dell'altare. Questo richiama l'attenzione sull'importanza di ciò che c'è dietro; la possibilità di ciò che è contenuto dal muro o dal velo oscurante. La tovaglia dell'altare stessa segna un contrasto con la superficie uniforme e bianca del tabernacolo: è ricoperta di parole rosse scritte a mano che, nella loro mano corsiva, fanno uso delle forme delle lettere come ornamento. Le linee nere dividono una ad una le parole sul tessuto, rispecchiando le linee bianche dei mattoni del tabernacolo. Ciò suggerisce la possibilità di una connessione tra le parole, contenute nei mattoni della tovaglia dell'altare, e il mistero di ciò che contiene il tabernacolo.

Tradizionalmente, è l'Eucaristia, il Corpo e il Sangue di Cristo, che è conservata, oscurata, dalle pareti del tabernacolo. La dimora temporanea dell'Eucaristia, qui, fa eco alla dimora temporanea di Cristo tra gli uomini: il periodo temporaneo in cui “il Verbo si fece carne e venne ad abitare in mezzo a noi”, così come le parole stesse danno la caducità di un'idea un corpo (carne) temporaneo. In effetti, sant'Agostino utilizza la natura del linguaggio per descrivere la natura dell'anima umana. Afferma che in una parola, “in analogia ad un essere animato, il suono è corpo e il significato quasi anima del suono”. Ciò indica un parallelo tra i luoghi di dimora temporanea: le parole sono corpi e i corpi sono luoghi di dimora temporanea. Il tabernacolo è un corpo ed è una parola, e il suo corpo potrebbe essere usato come simbolo della natura delle parole come corpi. Martin Heidegger, discutendo della poesia di Friedrich Hölderlin, suggerisce che le parole sono potenziali spazi abitativi: “La creazione poetica, che ci permette di abitare, è una sorta di edificio”. È questo collegamento alla natura delle parole su cui commenta il lavoro di Peake. Il tabernacolo contiene e nasconde; allo stesso modo, le parole sulla tovaglia dell'altare, molte delle quali sono oscure (rari), sono superfici che velano qualunque significato contengano. Scritte come ornamento, le loro curve e linee sono veli decorativi che avvolgono un mistero.

Queste parole decorative sono pensate per essere guardate piuttosto che lette, e il loro compito in questo modo è assicurato dalla difficoltà di leggerle. Non solo sono parole oscure in mano corsiva, ma molte di esse utilizzano la scrittura a specchio, che forza una considerazione della direzione. Sebbene neghi qualsiasi tentativo di leggere da sinistra a destra, le parole non vengono mai riflesse sull'orizzontale; corrono verso il basso, dirigendo l'occhio sempre più in basso, indicando il pozzo centrale della cappella. Questo buco, nero e senza superficie, diventa un altro specchio del tabernacolo bianco e murato. Parimenti, questo pozzo contiene, evoca e significa, e attorno ad esso sono state costruite le mura della cappella stessa, per contenerlo, dandogli un luogo di dimora.

Gertrude Gibbons Settembre 2020

[i]John 1:14.

[ii]Saint Augustine, The Greatness of the Soul: The Teacher. Translated by Joseph M. Colleran, Paulist Press, 1950, p. 94.

[iii]Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought. Translated by Albert Hofstadter, Perennial Classics, 2001, p. 213.